Doctor, Am I Crazy?

By Dr. Kenneth Light

Spinal-related disorders are not only the most common ailments affecting our society; they are among the most painful and most misunderstood by the medical profession. An example of this is patient Ron Miles. Six months after an emergency disc surgery, Ron was in so much pain he seriously contemplated suicide. His doctor prescribed pain medication, but his condition continued to deteriorate. Ron consulted with his doctor, but the response he received made Ron more despondent. "My doctor thought I was crazy, that my pain simply couldn't be that bad; he didn't believe me!"

Many orthopedic and neurosurgeons are uncomfortable at the thought of seeing back pain patients. Doctors sometimes display frustration by acting aloof, conveying to the patient that their problem does not warrant their skill, or denying that the patient they performed a perfectly good operation on still has pain. The problem is that doctors cannot agree on the diagnosis. Does a patient have a bulging disc, a herniated disc, or a degenerative disc? Does a patient need surgery, or can he/she be treated conservatively? If a patient needs surgery, doctors cannot agree on what is the most successful operation, and if the patient has pain afterward, they cannot agree on the potential cause of the problem and what should be done to correct it.

The confusion among the medical specialties manifests itself as frustration and even despair in our patients. Many of my patients search for years, travel from doctor to doctor, hoping someone will believe that their problem is real, that they are not confabulating a "tall tale" just to obtain narcotics or swindle a fortune out of the worker's compensation system. Doctors who suggest to their patients that "it's all in their mind" further contribute to their medical problem, not solve it. The fact is, many doctors are inexperienced at evaluating and treating patients who have had prior surgery. We must be reminded of what we learned early on in medical school: listen to the patient!

When I first saw Ron Miles, I felt that his condition was serious and needed immediate attention. I reviewed his test, which showed only a very small problem. The test, however, did not correspond to his complaint, and his pain was out of proportion to his myelogram. I believed him. Due to his young age of 32, we decided to repeat the test with a technique that relies on the radiologist injecting dye into the disc and into the dural sac. Performing this test sometimes allows the doctor to differentiate scar tissue from disc tissue. Sometimes, it can even separate a malingerer from a patient telling the truth. The next day, I received a phone call from the radiologist confirming the fact that Ron Miles had one of the largest herniated discs he had ever seen, proving the patient's level of discomfort had been warranted. I asked Ron to return to my office with his family to discuss the potential risks and benefits of the proposed corrective surgery. His decision was to have the operation, which consisted of a repeat laminectomy, a discectomy, posterior lateral fusion with pedicle screws and rods, and a repair of the pelvis using iliac allograft.

On his fifth hospital day, the day of discharge, he was out of pain, and the surgical procedure was successful. He recounted how he had spent one year trying to get someone to listen to him. This 250-pound, fully bearded man walked up to me, put his arms around me, and said, "Dr. Light, thank you for giving me my life back."

When the MRI Lies

By Dr. Kenneth Light

Magnetic resonance imaging is the single greatest advancement in the diagnosis of spinal pathology since the introduction of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895.6 MRI provides the clinician with a precise picture of the pathologic anatomy of the spine.2,4,5,7 The technique has been maligned because of its lack of specificity, particularly in patients over 60, where up to a 57% false-positive rate has been reported.1 This should not come as a surprise since we have known for years that the clinical symptoms of acute disc herniation and spinal stenosis can be transient, leaving the patient with a demonstrable pathologic lesion asymptomatic.3 It is up to the clinician, not the radiologist nor the MRI scanner, to decide whether the anatomic lesion discovered by the test is clinically significant.1,8

Over-reliance on the test alone can lead to an erroneous conclusion, a mistaken diagnosis, and an unhappy patient. The following case illustrates this point.

Case Report:

M.D. is a 45-year-old controller for BART who has been disabled for l-l/2 years with a chief complaint of low back pain radiating to the left leg, top of the foot, and great toe. Since l982, the patient has had low back pain effectively managed by chiropractic manipulation. Two years ago, the pain intensified. He was given four caudal steroid injections, medication, hypnosis, TENS units, and acupuncture, and eventually had a two-level microscopic discectomy. The procedure failed to remove all the extruded fragments, and the operation was repeated l0 months later. He felt better for one month, when the pain increased to the point that he had to use a cane because of a slapping sensation he noted with his left foot. The dorsum of his left foot became entirely numb, and he was unable to walk one block, stand for 10 minutes, sit for 20 minutes, or sleep because of left leg pain. He was forced to take four Vicodin tablets per day. An MRI scan was done and revealed "scar tissue enhanced with gadolinium, no evidence for recurrent disc herniation." (fig.1, fig.2)

He was told nothing could be done, and his insurance carrier planned on having him declared permanent and stationary, discontinuing his medical treatment.

Physical Examination:

The physical examination showed tenderness at the L4-5 level. Forward flexion: Hands to thighs. The patient was unable to walk on the heel of his left foot and had decreased sensation to pin on the dorsum of his left foot. The straight leg raising test and bowstring sign on the left produced pain propagating toward the outside of the ankle.

Further testing in the form of pyelogram-histogram-CT scan showed that the material felt to be scar tissue on the gadolinium enhanced MRI was really a sequestered disc fragment responsible for the patient's leg symptoms. (fig. 3)

Removal of the fragment and fusion of the spine was carried out with complete resolution of the leg pain, numbness, and foot drop. (fig. 4, 5, 6)

Discussion:

The MRI is a powerful new tool that creates a precise anatomic image of the spine. This test, like the myelogram and CT scan before it, is not a substitute for a careful history and physical examination. 3,8 The MRI demonstrates the pathologic anatomy. It is up to the clinician to decide whether the abnormality is the cause of the patient's symptoms or not.

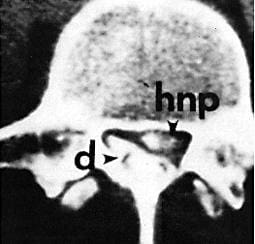

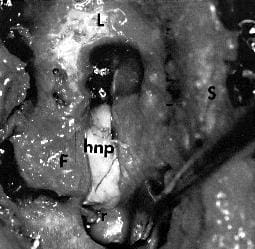

Despite two microscopic discectomies that failed to adequately expose and remove the herniated disc over an 18-month period, this patient had unequivocal signs and symptoms of a herniated disc at L4-5. Severe leg pain, which radiates to the outside of the ankle with numbness on the top of the foot and great toe and a foot drop, is highly suggestive of a disc extrusion at L4-5 with L5 root entrapment. The positive straight leg raise and bowstring sign are also suggestive of a mass effect on the dural sac and L5 root, and not of scar tissue (fig. 2). The speckling and enhancement with gadolinium seen on the MRI scan, which theoretically should not occur with an extruded disc fragment, caused the radiologist to make the erroneous diagnosis of scar tissue. In the setting of prior surgery, such reports should be carefully scrutinized by the clinician, who should also review the study firsthand. In this case, scar tissue that grew around the fragment led to the misdiagnosis. The clinical signs and symptoms in this instance led to the myelogram, diskogram, and CT scan. Injection of the L4-5 disc caused severe leg pain, which corresponded to the patient's complaint. A Subsequent CT scan showed the sequestered fragment, which later was confirmed at surgery. (fig. 3, 4)

Figure 1.

Sagittal T1 weighted image. Cerebrospinal fluid appears dark, as does a degenerative disc, a recurrent disc herniation, or scar tissue, making the diagnosis difficult. This scan was interpreted as normal by the radiologist.

Figure 2.

Axial image at the level of the pedicle enhanced with gadolinium. Note aural sac (d). Arrowhead > points to soft tissue, "speckled" and enhanced by gadolinium. Is this scar tissue? Or recurrent disc herniation? This was erroneously interpreted as scar tissue because of "the speckled appearance" and "bright signal."

Figure 3.

"Myself-disco-CT", at the same spinal level as the MRI. Dye is injected into the aural sac (d). Dye was also injected into the disk, which reproduced left leg pain radiating to the outside of the ankle. Dye is absorbed by sequestered (hnp) > and shows fragments erroneously diagnosed as scar tissue by gadolinium-enhanced MRI scan.

Figure 4.

Actual view at surgery. (F) Facet joint, (L) Lamina with laminotomy, (S) spinous process. Note large (hnp) severely compromises the left L5 root (r).

Figure 5.

The actual fragment at surgery measures 4x1 cm.

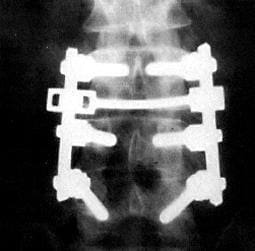

Figures 6 and 7.

AP and lateral postoperative x-ray. Removal of recurrent L4-5 disc is treated with a fusion of the spine and fixed with intrapedicular screws and TSRH rods and cross-link to prevent third recurrence and symptomatic mechanical back pain, which commonly follows excision of the recurrent disc.

References

1. Bolden, S., Davis, D., Dina, T., et al.: Abnormal MRI scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. J. Bone Joint Surg. 72A: 403-409, 1990

2. Edelman, R.R.: High-resolution surface coil imaging of lumbar disc disease. A.J.N.R. 6:479-485, 1985

3. Hitselberger, W.E. and Witten, R.M.: Abnormal myelograms in asymptomatic patients. J. Neurosurg., 28:204-206, 1968

4. Modic, M.T., Masaryk T., Boumphrey, F., et al.: Lumbar herniated disc disease and canal stenosis: prospective evaluation by surface coil MR, CT, and myelography. A.J.R. 147:757-765, 1986

5. Maravilla, K.R., Lesh, P., Weinreb, J.C.: Magnetic resonance of the lumbar spine with CT correlation. Am. J. Neuroradiol., 6:237-245, 1985

6. RÖntgen, W.C., Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen. [Vor lÄufige Mittheilung] Sitzgsber. Physik.-med. Ges. Wurzburg., 137:132-141, 1895

7. Schnebel, B., Kingsten, S., Watkins, R., and Dillin, W.: Comparison of MRI to contrast CT in the diagnosis of spinal stenosis. Spine 14:332-337, 1989

8. Wiesel, S.W., Tsournas, Nicholas, Feffer, H.L., Citrin, C.M., Potronas, Nicholas: A study of computer-assisted tomography. The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine 9:549-551, 1984